Chat Control & Going Dark: The war on encryption is on the rise. Through a shady collaboration between the US and the EU.

State mass surveillance

After Snowden’s whistleblowing in 2013, large parts of the internet became encrypted, enabling private and secure communication. Not everyone has welcomed this change. Most notably, the FBI and other U.S. government agencies have fought what is often called the “crypto wars”, the war on encryption. In recent years, they have been joined by the European Commission. Under the slogan “what about the children,” they try to introduce total mass surveillance of all EU citizens — first through the proposed Chat Control legislation, and later via the Going Dark and ProtectEU initiatives. The goal is to legally mandate spy tools on every European smartphone and computer. The forces behind these efforts have turned out to be American tech companies and intelligence agencies.

On May 11, 2022, EU Commissioner Ylva Johansson presented a legislative proposal under the official name ”Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down rules to prevent and combat child sexual abuse.”

Ylva Johansson made a point of this being her bill: it was she who had devised it – no one else – and if it had not been for her, Europe’s justice system would “go blind” in the hunt to track sexual abuse of children. In Ylva’s world, the EU would “turn into a pedophiles’ paradise” if she didn’t get her way. It was easy to marvel at how, on almost every occasion, Ylva Johansson was keen to point out that this was her proposal. A touch of narcissism? Maybe. But perhaps there was something else behind this self-centered proclamation. Because it would eventually emerge that in fact Ylva Johansson was not alone behind the scenes. Right from the start, there were others involved – actors who would benefit from the bill being passed, but who preferred it not to be known that they were involved in designing it.

The rhetoric was clear from day one: it was all about the children, and when it comes to children, there’s nothing we can’t imagine doing to keep them safe. So Ylva Johansson put forward a proposal that meant total surveillance of all EU citizens and as soon as someone opposed it, she pulled out the think-of-the-children card. But those who could see through the bluff quickly gave the proposal (those parts of the bill that dealt with internet surveillance) a shorter and more appropriate name: Chat Control.

In brief, Chat Control essentially meant that the communications of every EU citizen would be monitored. Every call, every message and every chat, all the emails, photos, and videos saved in cloud services – all of it would be filtered in real time via artificial intelligence and then checked in a newly established EU center, in close cooperation with Europol.

Since the bill was in violation of the European Convention on Human Rights, the EU Charter and the UN Declaration of Human Rights, Chat Control was rejected by one legislative body after another. Both the Council of Ministers and the European Commission’s own legal service warned against the proposal, as did the European Parliament’s Data Protection Board. The UN Human Rights Council described Chat Control as incompatible with fundamental human rights and stated that the proposal would lead to mass surveillance and self-censorship. Former judges at the European Court of Justice said that the proposal was in breach of the EU Charter of Rights and 465 researchers joined forces to warn of the consequences.

Faced with massive criticism, Ylva Johansson defended herself. According to her, everyone else had misunderstood the bill. Chat Control was certainly not about mass surveillance and everyone making that claim was simply out to discredit her.

Chat Control – total monitoring of all EU citizens.

Chat Control is sometimes also called Chat Control 2.0, since existing legislation already makes it possible for tech companies such as Google and Meta to scan their users’ accounts for child pornography material. The fact that there was already a law that allowed tech companies to scan for illegal content – if they chose to – was something Ylva Johansson was not slow to mention. She explained that her draft bill was nothing but an extension of the scanning that had already been going on for ten years. She also referred to the existing legislation when she said that the EU would become a free zone for pedophiles unless her bill went through – as that legislation would expire in the summer of 2024.

Time and time again Ylva Johansson was proven wrong by journalists and experts. In fact, nothing prevented the EU from extending the existing law, rather than introducing a new one. And above all: Ylva’s bill was anything but an extension. The differences between the current law and the proposed legislation were extreme. In Ylva Johansson’s EU, scanning would not be voluntary. All messaging services (including encrypted services such as Signal) would be covered by the law and would be forced to scan their users’ images, videos and conversations. That would be a big concern for all those who don’t use Meta or Google to converse because they are in need of secure communication methods. In other words, political opponents, whistleblowers, journalists and their sources, vulnerable people living under secret identities and others, not to mention people with trade secrets, and those in possession of sensitive information important for national security. For example, the European Commission itself uses Signal. Demanding government transparency (either through so-called backdoors or scanning on the computer or phone) would open a Pandora’s box to countries with authoritarian inclinations (and five EU countries have already been caught using spyware to monitor political opponents) and would leave the door wide open for criminals to exploit. But it was not only this that separated the existing legislation from the draft bill that the European Commission wanted to introduce.

The previous legislation had only allowed scanning for material that had previously been stamped and registered as child pornography material. Now, AI would be used to find ‘new material’ and would also look for grooming attempts. Quite obviously, Chat Control would therefore send every other citizen of the EU straight into the filtering system. Holiday photos from the beach, nude photos sent between partners, dirty text messages – all the things that no AI system can distinguish between would risk getting caught in a filter that would inevitably drown any new EU center with endless digital heaps of evidence to review. Is this a holiday photo of a child or child pornography? Are these skimpily dressed youngsters 18 or 14? Is this a dirty text message from a wife to a husband or a grooming attempt? But above all, Chat Control would mean a tool that could be used to scan for completely different things.

When Ylva Johansson was asked whether it would be possible to communicate safely even after her bill was introduced, she answered “Yes.” And a whole world of experts asked “How?” Ylva replied that she had something nobody else had. A digital sniffer dog that could smell encrypted communication without looking at the content. A sniffer dog that only reacted to child pornography content – never anything else.

A group of experts tried to hammer the message home: either encrypted communication is encrypted (so-called end-to-end encryption, which means that only the sender and the recipient can see the communication; not even the service provider has access to it) or it’s not encrypted. There’s no ‘seeing the content’ without reading it. But Ylva stood by her claim. She came back to the same argument over and over again. She avoided answering the questions (she obviously didn’t understand how the technology worked) but instead turned the direction of the discussion, saying, for example, that a court order would be required to carry out scanning, which in itself was deliberately misleading. Firstly, her scanning would not require an order from a court – it could be one from another judicial body. And secondly, the key issue was that judicial body making a decision that would force messaging services to monitor all their users. So in other words, when Ylva proclaimed “it requires a court order,” she wasn’t talking about courts and their decisions to monitor people such as suspected pedophiles. She was talking about how a service would be forced to permit surveillance. What was required for a service to be subject to surveillance? Merely that there was a possibility to use the service to spread child pornography or to groom children. Which of course means every messaging service on the planet.

As soon as Ylva Johansson was shown to be in the wrong, she shifted her focus. But in the end, she always came back to the final refuge: it’s all about the children. She related anecdotes and referred to figures that pointed to an exponential increase in child pornography material on Facebook, for example – even though Facebook itself stated that 90 percent of all reports come from material previously distributed.

The European Commission, led by Ylva Johansson, received criticism from all directions. Police chiefs pointed out that most of the material they receive today involves teenagers sending pictures to each other and that such reports risk leading the police in the wrong direction. Scanning tests carried out by European police on existing material showed that 80-90 percent of all hits were false positives. Now, moreover, ‘new material’ would be scanned – which would obviously mean an impossible administrative burden merely to distinguish between illegal images and holiday pictures from family days on the beach. The error rate would clearly be approaching 100 percent. For a European justice system that even today is unable to follow up all the tips it receives, this would be devastating. And criminals would, of course, turn to illegal messaging services. No children would be helped. At the same time, every EU citizen would have spyware installed on their phones.

How did Ylva Johansson deal with this information? Not at all. Instead, like a scratched record, she continued urging everyone to “think of the children.” She also ordered a survey that said 80 percent of the EU population supports Chat Control. The problem? The European Commission used its Eurobarometer series of public opinion surveys in a way that opened it to accusations of blurring the line between research and propaganda. When asked to comment on the Chat Control survey, the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies concluded that it had a political agenda and consisted of questions that were biased to support the Commission’s plans.

Ylva Johansson was employing blatant deception. She used incorrect figures and biased surveys. In interviews, she was populist and evasive. But she was forced to resort to these methods. Because it was never about the children.

American tech companies and security services behind the draft bill

In September 2023, a major investigative article was published by three journalists: Giacomo Zandonini, Apostolis Fotiadis, and Luděk Stavinoha. After seven months of trying to get the European Commission to release public documents, they finally obtained a piece of material that allowed them to start putting together the puzzle. The puzzle that revealed the true stakes behind Chat Control. The article, which was published in several European newspapers, included a letter in which Ylva Johansson wrote to Julie Cordua, CEO of the American company Thorn: “We have shared many moments on the journey to this proposal. Now I am looking to you to help make sure that this launch is a successful one.”

Thorn is an American company, formed by actor Ashton Kutcher, which develops tools that scan for child pornography material. Thorn had sold software worth millions of dollars to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Ashton Kutcher himself had held video conferences with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, and had given lectures in the EU on how new technologies can scan encrypted content without looking at it. The picture of Ylva Johansson’s digital sniffer dog suddenly became clear.

For several years Kutcher lobbied the European Commission (until he was forced to resign as chairman of Thorn’s board after defending his acting colleague Danny Masterson when he was convicted of rape). He held meetings with others at the European Commission and had an extra close relationship with the Parliaments’s Eva Kaili (until she was arrested for bribery and forced to leave her party).

So here was an American company in direct contact with the European Commission. An American company that just happened to sell the technology that could be used if Chat Control was introduced. In addition, it was all based on a false premise. The technology Kutcher and Johansson talked about did not exist. Expert after expert condemned their talk of sniffer dogs.

And here’s yet another seedy aspect to this scandal: in the EU transparency register, Thorn was registered as a charitable organization – despite selling the technology they were lecturing about in the EU. The trick of disguising organizations and corporations as charities would turn out to be a recurring motif.

Since the draft Chat Control bill was presented, Ylva Johansson has constantly referred to children’s rights organizations that support her proposal. She has worked with them in a PR context, as a way to show how Chat Control has the support of independent, nonprofit organizations that care about children. A central organization in this work has been the WeProtect Global Alliance. When Zandonini, Fotiadis, and Stavinoha published their article, it turned out that the European Commission had been involved in founding this organization, and that it included representatives from both tech companies and security services in different countries. Ylva Johansson’s colleague in the European Commission, Labrador Jimenez, was on the Board of Directors of WeProtect, together with Thorn’s CEO Julie Cordua, representatives of Interpol, and government officials from the US and the UK (the latter simultaneously pursuing its own monitoring legislation, also using children as the battering ram). Thorn had put a great deal of money into WeProtect. The European Commission had contributed one million euros. In other words, it wasn’t children’s rights organizations that were supporting Ylva Johansson. It was lobbying organizations set up by the European Commission to get the bill through.

The Board of Directors of WeProtect also included representatives from the Oak Foundation, who, in addition to their involvement in WeProtect, had also been involved in setting up ECLAG (another charity that supported the Chat Control proposal). ECLAG was launched just a few weeks after Ylva Johansson’s draft bill was presented, and Thorn was also represented on this organization’s board. And there was still another organization: the Brave Movement, an organization formed a month before the proposed Chat Control bill was introduced. Brave was launched with $10 million from the Oak Foundation and a strategy paper discovered by the journalists stated that “once the EU Survivors taskforce is established and we are clear on the mobilized survivors, we will establish a list pairing responsible survivors with Members of the European Parliament – we will ‘divide and conquer’ the MEPs by deploying in priority survivors from MEPs’ countries of origin.”

The Oak Foundation also appeared in an article carried out by the Intercept. In 2023, an American organization called the Heat Initiative was formed. On paper, they were a “new child safety group” and the first thing they did was campaign for Apple to “detect, report, and remove” child pornography material from iCloud. Apple responded that this would be something that criminals would be able to exploit and that it could also lead to a “potential for a slippery slope of unintended consequences. Scanning for one type of content, for instance, opens the door for bulk surveillance.”

The Heat Initiative did not like this answer and fought back with anti-Apple propaganda on large advertising billboards in American cities under the theme of ‘think of the children.’ But who was behind the Heat Initiative, besides the Oak Foundation? Heat was led by a former vice president at Thorn. The Intercept article also referred to the fact that Thorn was working with Palantir, the big-data company that helped the NSA mass-monitor the whole world and was involved in the Cambridge Analytica scandal where Facebook users’ private messages and data were used to influence the presidential election on behalf of Donald Trump in 2016.

In other words, the European Commission was involved in funding and starting up charities with the aim of exploiting existing victims to emotionally influence EU parliamentarians. In close cooperation with the tech company providing the technology that would be used in the implementation of the monitoring. Together with representatives of non-European security services. As part of a larger apparatus, where the same tactics were used to influence developments in the United States.

At the same time, the real organizations working to counter sexual crimes against children were wondering why the European Commission was refusing to talk to them. In the same investigative report, Offlimits, Europe’s oldest hotline for vulnerable children, tells how Ylva Johansson would rather go to Silicon Valley to meet companies interested in making huge profits than talk to them.

The same is true of the technical experts. Matthew Green, Professor of Cryptography at John Hopkins University, said: “In the first impact assessment of the EU Commission there was almost no outside scientific input and that’s really amazing since Europe has a terrific scientific infrastructure, with the top researchers in cryptography and computer security all over the world.”

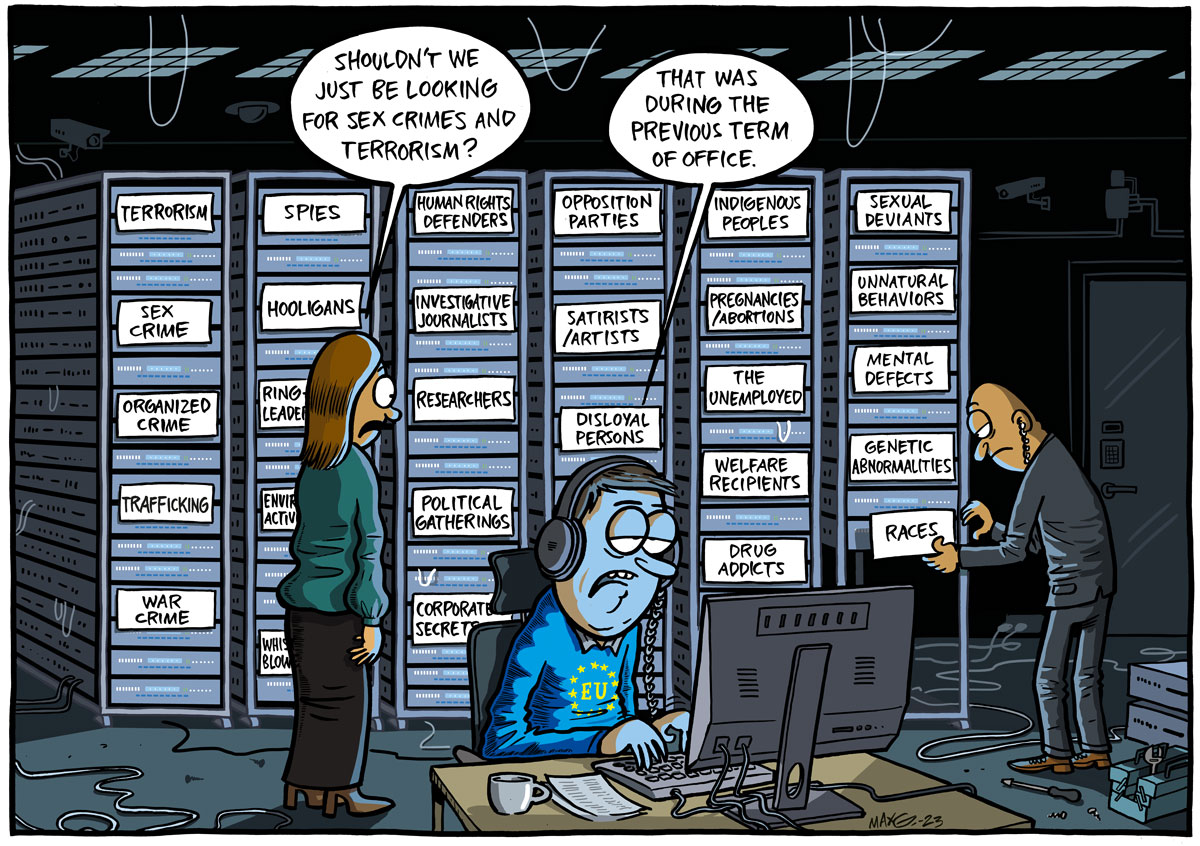

However, Europol was involved in drafting the law, together with security services from other countries. In July 2022, Europol wrote that it wanted to be able to use scanning and surveillance for purposes other than sexual offenses against children. The European Commission responded that it understood the wish but that it had “to be realistic in terms of what could be expected, given the many sensitivities around the proposal.” Thorn was also clear in understanding that the scanning could later be used for other purposes: “When considering regulation or legislation on encryption it should not be done solely focusing on CSAM. Solutions for detection in encrypted environments are much broader than one single crime,” the company wrote in one document.

It was later revealed that Europol was looking for unfiltered access to the scanned material: “All data is useful and should be passed on to law enforcement. There should be no filtering by the [EU] Centre because even an innocent image might contain information that could at some point be useful to law enforcement.”

European Parliament: “the commission wanted mass surveillance.”

So here was the European Commission, working on legislative proposals together with a Europol that wanted access to all surveillance, regardless of whether it contained something illegal or not – simply because it could be useful to have. In other words, it really wasn’t about the children.

When articles were published about the EU Commission’s horrifyingly undemocratic approach, Ylva Johansson’s office at the European Commission responded by advertising on the platform X (formerly Twitter). They targeted advertisements (pro Chat Control) so that decision-makers in different countries would see them, but also so that they would not be seen by people suspected to be strongly against the proposal. The advertising was also targeted on the basis of religious and political affiliation and thus violated the EU’s own laws regarding micro-targeting.

Officials at the highest EU level thus used data collected by big tech to try to create illegal filter bubbles designed to push through a mass surveillance proposal. The whole thing ended with Ylva Johansson being summoned to a hearing in the European Parliament. An almost united European Parliament was massively critical of Ylva Johansson and her approach. She was grilled about Thorn’s interference and about the targeted ads and the EU Ombudsman denounced the European Commission’s unwillingness to share public documents regarding the relationship with Thorn (the European Commission had assumed these would be classified because they risked undermining commercial interests …) Ylva Johansson’s answer? “Think of the children.”

In November 2023, the European Parliament’s statement was delivered. In an almost historic consensus, all the groups in the Parliament stood together and said “No” to the bill. At the press conference, representatives from the Parliament said: “This is a slap in the face of the Commission, what we’ve tabled. The Commission wasn’t focusing on protecting children but wanted mass surveillance.” Patrick Breyer, who has been the most active opponent in the EU Parliament, called it a victory for the children, adding “They deserve an effective response and a rights-respecting response that will hold up in court.”

Breyer was referring to the fact that Chat Control would most likely not hold up in court if the bill had been passed. Just a few months later, a ruling from the European Court of Justice ruled that authorities do not have the right to demand access to end-to-end encrypted communications.

The Parliament’s clear stance against chat control did not mean the fight was over. In the EU, two bodies are involved in the adoption of legislative proposals made by the EU Commission: the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers. Unfortunately, in the Council of Ministers, the tone was different. While the Parliament strongly opposed the proposal, unified in its stance, the Council continued to struggle to reach a common position. Time and again, they tried to come up with compromise proposals that would essentially result in the implementation of chat control. However, it became evident that not even the Council of Ministers believed in Ylva Johansson’s digital sniffer dog, as parts of the Council proposed that scanning should be excluded for politicians, police and intelligence services, as well as anything classified as “professional secrets.” Obviously, there were politicians who were afraid that their secrets would leak, but who had no issue with mass surveillance of the broader population. Patrick Breyer was clear in his response: “these people are aware that Chat Control involves unreliable and dangerous snooping algorithms – and yet they are ready to unleash them on us citizens.”

As a unified stance from the Council of Ministers was delayed, the deadline Ylva Johansson had mentioned in the debates was approaching. She had repeatedly argued that the EU would “go dark” in the fight against criminals if chat control was not adopted – since the current legislation (the voluntary scanning) would expire in the summer of 2024. Did she then go public in the summer of 2024 and declare it was over? Of course not. She quickly and easily did what had previously been completely out of reach in her argumentation: she extended the previous legislation.

New attempt at mass surveillance via the Going Dark initiative

While the EU member states in the Council were trying to come up with various compromise proposals to implement chat control, they were also working on a plan B and new attempts for mass surveillance legislation. During Sweden’s EU Presidency in spring 2023, a project called Going Dark was initiated. The idea from the Swedish Presidency was initially that a so-called High Level Expert Group would be launched. The task of putting together the group went to the European Commission, which immediately removed the ‘Expert’ label. Instead of a High Level Expert Group, a High Level Group was formed. As the Netzpolitik newspaper put it: “Removing the word ‘expert’ is no small detail: special rules apply to Expert groups, for example when it comes to transparency. Rules that do not apply to High Level Groups.”

Once again, the European Commission chose to start the preparatory work linked to mass surveillance without allowing experts to play a serious part in the process. When the group met for the first time, it stated that the group’s purpose was to discuss methods to achieve “access to data for effective law enforcement, based on and guided by the inputs from the EU Member States.”

Some challenges were identified as particularly pressing: access to encrypted material (both stored data and communication), data storage, location data, and anonymization (including VPNs and Darknets).

The group was divided into three working groups: the first would work with access to data on users’ devices (computer and mobile), the second group would focus on access to data in the services’ systems (messaging apps, for example), and the third group would discuss access to data in transit.

According to the minutes of the meeting of the Swedish Parliament’s Committee on European Union Affairs, the group worked “to present effective recommendations for the accession of the new Commission in 2024 and for those recommendations to be implemented.”

Future legislative proposals from the European Commission could thus be assumed to be about providing access to data on users’ devices and in the messaging services’ systems, and to data in transit. Patrick Breyer, who had worked hard to counter Chat Control, said the group was just an extension of past offensives and that Going Dark was working to introduce illegal mass surveillance. When he requested documents from the group’s meetings and a list of the attendees, he received a document with the information blacked out as if classified. The European Commission had thus put together a working group aiming to achieve mass surveillance of the broader population while not being transparent about who was part of the group. It was like a scratched record. Gone was the old excuse “think of the children”, but the goal was the same.

However, some transparency was obtained through the Swedish Ministry of Justice, which at Mullvad VPN’s request provided both meeting notes and information about the Swedish representatives present at the meetings.

The first Going Dark meeting was led by two people. One was Olivier Onidi, who is Deputy Director General directly under Ylva Johansson in the European Commission. Onidi has expressed that the “valuable” thing about Chat Control is “to cover all forms of communication, including private communication”, and he defended Ylva Johansson and Chat Control when he said: “I think it’s totally unfair to point this out as a mandatory inspection of all private communications. That’s not what you have in front of you. This proposal is a huge improvement over the current situation.”

Onidi has also been questioned for his meetings with the American company Palantir (notorious for its involvement in US authorities’ illegal mass surveillance).

The second person who led the first Going Dark meeting was Anna-Carin Svensson, international chief negotiator at the Swedish Justice Department, who, according to WikiLeaks documents in 2010, allegedly urged the US State Department and the FBI to continue with the current informal exchange of information between the countries instead of signing formal agreements. According to the American representatives at the meeting, it was about withholding information from the Swedish Parliament:

“She believed that, given the Swedish Constitution’s requirement to present matters of importance to the nation to the Swedish Parliament, and in light of the ongoing controversy over the newly decided FRA law [FRA, Försvarets radioanstalt, the Swedish National Defence Radio Establishment, is a Swedish government signals agency], it will be politically impossible for the Minister of Justice not to let the Parliament review any data exchange agreements with the United States. In her opinion, the publication of this could also jeopardize the informal exchange of information,” the leaked documents said.

According to the documents, Anna-Carin Svensson asked the FBI if they could not continue to make use of the strong but informal arrangements. When the documents leaked, Svensson denied everything and stated: “I cannot be held responsible for how Americans express themselves.”

From the Swedish side, the Ministry of Justice was represented at the Going Dark meetings, but so was the Swedish Security Service (Säpo) and the Swedish Police Authority. Together with representatives from the other Member States, they used the High Level Group meetings to discuss how, through legislation, encrypted services could be required to provide data in readable format. Several Member States argued that “the working groups needed to look at solutions that involved ‘legal access through design’.” This was something that pleased American representatives.

At the Going Dark meeting on November 21, 2023, a former FBI employee was also present, who said that “solutions for legal access should be prioritized” and that “companies needed to have a responsibility and follow the same rules.” As a former FBI employee, he also expressed “his gratitude for the fact that the issue was being pursued within the EU.”

European police chiefs: we cannot accept criminals using secure communications.

The Going Dark meetings resulted in an outcry from the assembled police chiefs of Europe. In April 2024 Europol published the challenge “European Police Chiefs call for industry and governments to take action against end-to-end encryption roll-out.” The declaration was a “direct extension of the Going Dark initiative” and, together, the European police authorities were clear that although encryption is “a means of strengthening the cyber security and privacy of citizens … we do not accept that there need be a binary choice between cyber security or privacy on the one hand and public safety on the other. Absolutism on either side is not helpful.”

It was as if Ylva Johansson’s sniffer dog had caught the scent again. In the absence of expertise, the Going Dark initiative tried to magic away the fact that end-to-end encryption is absolute – either you have secure communication or you don’t.

The assembled police chiefs claimed there were two key factors for achieving online security – which turned out to be direct repetitions of the reasoning in the Going Dark discussions. Number 1: so-called legal access to the tech companies’ stored data. Number 2: real-time scanning of illegal activity in tech companies’ services. Naturally, they said, all this would be done under strong protection and supervision.

Stefan Hector, a representative of the Swedish Police Authority, said that “a society cannot accept that criminals today have a space to communicate safely in order to commit serious crimes.” A week later, it was revealed that the Swedish police had been infiltrated and were leaking information to criminals.

Although the UN classifies encryption as a human right, the Going Dark initiative and the European police force were fighting to smash end-to-end encryption. Their first move actually came as a reaction to Meta rolling out exactly such encryption.

Europol’s move was only an initial indication. At the end of May 2024, the Going Dark initiative resulted in 42 recommendations to the European Commission. The document notes that encryption adds a level of complexity when it comes to accessing real time content data, specially from messaging services implementing an end-to-end Encryption. It states that law enforcement need access to data en clair (i.e. in plain text) through “lawful access without weakening privacy.” The Going Dark initiative emphasizes the principle of “security through encryption and security despite encryption” as a central tenet.

The Going Dark initiative shows the same tendencies as the chat control proposal. Once again, experts have been excluded from the discussions, and ministers and police representatives have once again missed the main point: either end-to-end encrypted communication is private and secure, or it is not.

The solution sought by the Going Dark initiative (just like chat control) is scanning that occurs before the communication is sent. They argue that this method does not break the end-to-end-encryption. Who cares? It breaks the entire purpose of end-to-end-encryption. If communication is scanned before it is sent, it is not private and secure.

The Going Dark initiative’s 42 recommendations discuss stricter consequences for messaging services that do not provide “lawful access” to their data. With the principle of “security through encryption and security despite encryption”, two methods for such access are obvious. The Going Dark initiative are either looking for so-called backdoors to the systems – where authorities have access to the services’ systems and where there are backdoors or “extra keys” to the end-to-end encrypted conversations. Or they are looking for so-called client-side scanning, a scan that occurs in the user’s app on the computer or phone itself. Client-side scanning could also occur on the operating system itself – which would be very pleasant for authorities since everything happening on the phone could be monitored in one sweep. Similar to how Microsoft has begun developing its feature Recall, a feature developed to take a screenshot of the screen every few seconds.

Implementing this type of state spyware on EU citizens’ phones would not only mean that everyone’s privacy is lost. It would also lead to significant security risks. By now, mass surveillance advocates should know this. The echoes from the chat control debate are literal. But it is also an echo of an older battle.

The Going Dark initiative is really just an extension of the so-called crypto war (the war against encryption) that US authorities have been involved in since the internet began. As Signal’s CEO Meredith Whittaker said in a keynote speech:

“Encryption was essential for the commercial internet. But law enforcement and security services saw any network resistant to government surveillance as a threat and a problem.”

The US authorities have already tested the backdoors that the European Going Dark initiative is now seeking. They have seen the evidence: it is impossible to implement backdoors in a secure way, without hostile states or hackers being able to exploit them. Edward Snowden revealed that the NSA spent $250 million a year getting tech companies to install backdoors in their services, which also exposed the risks of backdoors. In 2010, Chinese hackers managed to use a Google backdoor to get into Gmail. The same thing happened in 2005, when state surveillance of Vodafone was exploited by outside actors to bug the Greek Prime Minister, his Foreign Minister, Justice Minister, and a hundred other government officials.

The same thing happened again in 2024, when hackers exploited backdoors that U.S. authorities had installed in telecom companies such as AT&T and Verizon, gaining access to millions of Americans’ phone calls. The U.S. blamed China as responsible for the operation, which was named Salt Typhoon. The hackers obtained metadata (who called whom), text messages, and were even able to listen in on calls. Among those affected were members of Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign staff, as well as phones belonging to Donald Trump and JD Vance. After the attack became public, representatives from the FBI and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency recommended Americans use encrypted messaging services to protect themselves. But at the same press conference, the FBI representative also said that people should use “responsibly managed encryption.” According to the FBI’s own website, this means “encryption designed to protect people’s privacy and also managed so U.S. tech companies can provide readable content in response to a lawful court order.” In other words, the FBI encouraged the use of encrypted services – but only those that the FBI could still access (through the same kind of backdoors that the hackers had just exploited).

The Going Dark initiative might go for so-called client-side scanning instead; scanning directly in the apps on users’ phones and computers, or even scanning the entire operating system. Besides the fact that this surveillance method would bring state spyware to everyone’s phones, it is also doomed to fail from a security perspective. It would not be possible to keep the data private and secure. We know this because Apple, one of the world’s most technologically advanced and wealthy companies, has poured incredible resources into figuring out if it can be done in a secure and private way. But when Apple made its effort public, it took hackers just two weeks to break in. Apple abandoned the attempt and continue to say no to anyone who asks them to try this again – simply because it’s too easy to hack systems where client-side scanning is involved.

The Going Dark initiative’s ambition to introduce backdoors and client-side scanning are not compatible with EU laws and human rights. But instead of working on proposals that do not violate human rights, the Going Dark initiative will focus on propaganda to push through its upcoming legislative proposals. Leaked documents emphasize the importance of ”setting the right narrative” and developing a ”communication strategy that underlines that the recommendations aim to protect fundamental rights”. A quick recommendation: develop proposals that do not violate human rights – then just show them to the world.

The Going Dark initiative seeks legislation that has been deemed illegal and violates human rights. It is a late ripple effect following Snowden’s revelations, which changed the internet in many respects. After Snowden’s whistleblowing, encrypted websites (https) became standard. End-to-end encrypted messaging services like Signal saw a widespread increase in popularity. Apple started using strong encryption in its operating systems. From having virtually free access to people’s internet traffic (if they didn’t use a trustworthy VPN, that is) and from having been able to read people’s messages in plain text, the internet now became more difficult for US authorities to mass monitor.

In her lecture, Meredith Whittaker points to an important point: “Strong encryption was an important win. But the result of this win was not privacy. Indeed, the legacy of the crypto wars was to trade privacy for encryption – and to usher in an age of mass corporate surveillance. Because the power to enable – or violate – privacy was left in the hands of companies, not those who relied on their services. Companies that were incentivized to implement surveillance in service of advertising and commerce.”

For more than twenty years, so-called commercial mass surveillance has created some of the richest companies in the world. The fact that Meta is rolling out end-to-end encryption doesn’t mean they have abandoned their business model. But it was still sufficient for the European police chiefs, cheered on by the US authorities, to make a joint declaration demanding legal access to the content in secure and private communications. Meredith Whittaker again:

“In my view, the ferocity of the current attack on end-to-end encryption, and other privacy-preserving technologies, is very much related to a desire by some in government to return to the less fettered access to surveillance that they see as having lost post-Snowden.”

We can see the attack coming in Europe right now. But the movement is based in the United States. Back in 2014, just a year after Snowden’s revelations, FBI Director James Comey spoke of how “the challenges of real-time interception threaten to leave us in the dark, encryption threatens to lead all of us to a very dark place.”

The US authorities, which in 2014 had recently been caught spying on the entire world, used a particular expression when they began lobbying to regain access to easily controlling everything and everyone. FBI Director Comey argued that they had to get access, otherwise they would be ”Going Dark”.

ProtectEU – Chat Control and Going Dark Under a New Name

In November 2025, the EU Council finally reached a common position on Chat Control. The requirement for mandatory scanning (including end-to-end encrypted messaging services) was removed. The EU Council failed to implement mandatory mass surveillance. However, it laid the groundwork for mass surveillance in the future.

The Council’s version of Chat Control included voluntary scanning, vaguely worded legislation that may entail requirements for age verification and mandatory ID checks (even for end-to-end encrypted services), and an article stating that the requirement for mandatory scanning shall be reconsidered every three years. They also introduced a new infrastructure for blocking material, where it is up to each member state to block what they consider illegal. All in all, this indicates that the EU Council is aiming to build an infrastructure for mass surveillance, and the legislative proposal is written in a way that opens the door to it.

The European Commission and several member states continue to fight for mass surveillance. They are doing this through Chat Control, but also through other initiatives. In 2025, the European Commission took the next step when Going Dark was transformed into ProtectEU: A European Internal Security Strategy. ProtectEU was based on the recommendations of the Going Dark initiative, but the clumsy name was gone. So was the old excuse of “what about the children.” Instead, the Commission expanded its justification, now using terrorism, serious crime, and violent extremism as battering rams to push through mass surveillance. What the European Commission did here was take Chat Control and, rather than fixing the fundamental flaws of the proposal, simply rebranding it under a new name. Instead of listening to criticism from experts and citizens, it chose to continue with propaganda. ProtectEU was clearly a communications product in line with Going Dark’s “communication strategy that underlines that the recommendations aim to protect fundamental rights.” In the first ProtectEU document, launched in April 2025, it stated that the goal was to “identify and assess technological solutions that would enable law enforcement authorities to access encrypted data in a lawful manner, safeguarding cybersecurity and fundamental rights.” Ylva Johansson’s old “drug-sniffing dog” – the one that could somehow read encrypted communication without breaking the encryption – was back. Under Johansson’s successor, Magnus Brunner, the European Commission continued to pour time and resources into trying to legislate technologies that don’t exist. Franz Kafka himself could hardly have portrayed this development more surrealistically. It’s almost laughable, if it weren’t for the fact that the European Commission knows exactly what it’s doing – intentionally trying to enforce mass surveillance. There’s really no other way to interpret it, when year after year they refuse to listen to courts, experts, and their own citizens, and instead devote all their energy to misleading the public. As Edward Snowden once said, quoting his friend John Perry Barlow at the Freedom of the Press Foundation: “You can’t awaken someone who’s pretending to be asleep.”